- 28th January 2026

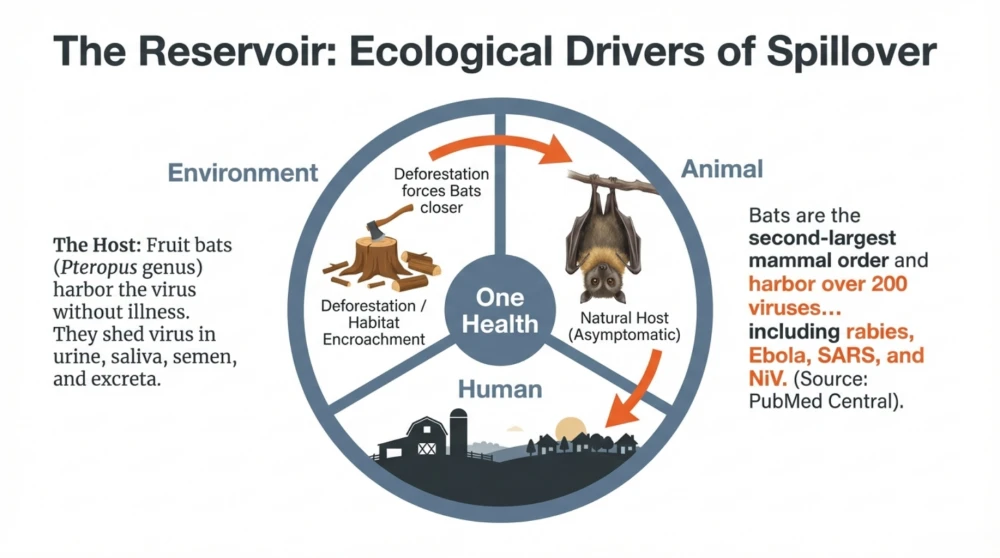

Recent headlines regarding the Nipah virus have naturally raised questions about global health security and our local preparedness. At the Dr. Pankaj Kumar Medical and Lifestyle Clinic, we believe that understanding these emerging threats is the first step toward collective safety. Currently, health experts are monitoring Nipah as a prime candidate for Disease X -- a term used for pathogens with significant pandemic potential. This heightened alert is not just about a single virus; it is a call for a One Health approach. By linking the health of people, animals, and our environment, we can address factors like deforestation and habitat encroachment that drive these spillover events.

To understand why this virus is making headlines, we must first look at its biological roots and its history in the animal kingdom.

What Exactly is the Nipah Virus?

The Nipah virus is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and Henipavirus genus. It is a zoonotic pathogen, meaning it primarily circulates in animals before jumping to humans. It was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore. While pigs were the initial bridge to humans in that event, the virus has also been found in horses, which acted as intermediate hosts during a 2014 outbreak in the Philippines.

The natural reservoirs for this virus are fruit bats, specifically those of the Pteropus genus, also known as flying foxes. These bats are symptomless carriers; they harbor the virus without falling ill. This lack of symptoms creates a silent threat because the virus can circulate unnoticed in bat populations until it finds a path into human communities.

Once the virus jumps to humans, its behavior changes from a silent stowaway to an aggressive invader. It has a specific pathogenic predilection for the central nervous system, which explains the severe brain inflammation seen in many patients. This aggressive nature is why the virus is categorized in the highest risk group, requiring maximum biosafety precautions for study.

Understanding the origin of the virus helps us identify the distinct pathways it uses to enter our daily lives.

The Transmission Trail: How it Spreads

Nipah entry into human populations occurs through distinct, identifiable spillover pathways. These events are often triggered when human activity brings us closer to the natural habitats of fruit bats.

The primary modes of transmission include:

- Direct contact with infected animals like bats, pigs, or horses.

- Consumption of food soiled by bat fluids, such as raw date palm sap or fruit with bite marks.

- Human-to-human spread through close contact with the respiratory secretions or body fluids of an infected person.

In the original 1999 outbreak, the virus was highly contagious among pigs, moving to humans who handled the animals. A critical clinical indicator for farmers is an "unusual barking cough" in pigs, which serves as a major warning sign. In contrast, recent clusters in Bangladesh and India have been linked to drinking raw date palm sap. Bats often visit collection jars at night, contaminating the liquid with saliva or urine.

As the virus moves from the wild into our homes, it begins to manifest through a series of increasingly severe clinical stages.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms

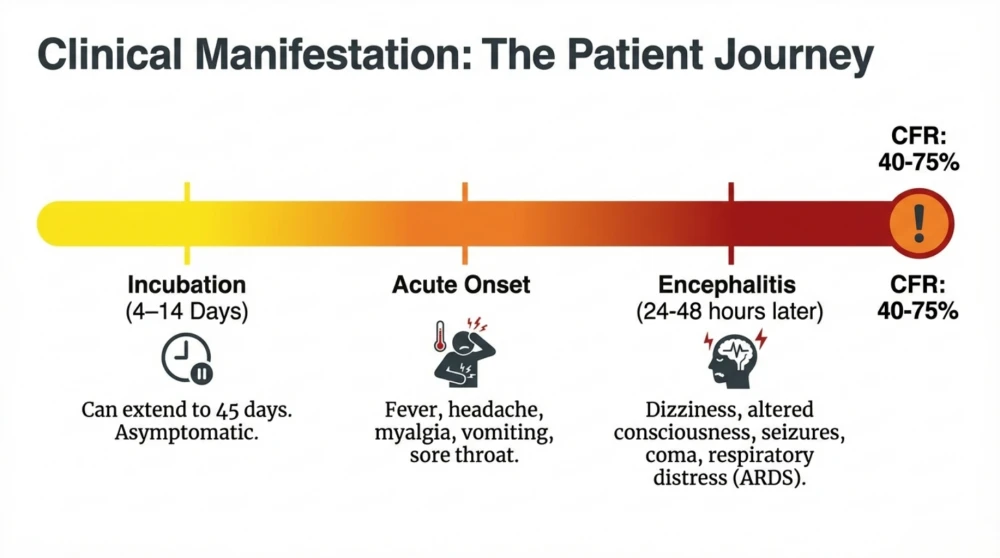

Early detection of Nipah is a strategic challenge because the initial symptoms are non-specific and often mimic a common flu. Patients typically begin to show signs 4 to 14 days after exposure. However, clinicians must remain vigilant for outliers, as incubation periods as long as 45 days have been documented in some cases.

The illness usually starts with fever, headache, muscle pain, vomiting, and a sore throat. Some patients also experience acute respiratory distress, presenting as a severe cough or difficulty breathing. Identifying the virus at this "flu-like" stage is vital for preventing further spread, even though the symptoms do not yet point clearly to Nipah.

If the disease progresses, it can quickly become life-threatening by causing encephalitis, or swelling of the brain. Symptoms of this stage include confusion, seizures, and unusual drowsiness. A patient can fall into a coma within 24 to 48 hours of these neurological signs appearing. The severity of the disease is reflected in its high fatality rate, which ranges from 40% to 75%.

Because the disease can escalate so rapidly, it is important to know which groups must maintain the highest levels of vigilance.

Who Should Be Careful?

Certain groups are at a much higher risk of exposure due to their professional or personal proximity to the virus. This is particularly relevant for those living in or traveling to the "Nipah belt," which includes regions in West Bengal, Kerala, and parts of Bangladesh.

Healthcare providers and family caregivers are on the front lines and face the greatest risk of human-to-human transmission. Because the virus is found in respiratory droplets and secretions, those in close contact with infected individuals must use strict safety protocols. This includes wearing masks, gloves, and protective clothing to block accidental exposure during patient care.

Travelers to endemic regions should also exercise caution. While the general risk remains low, one must avoid environments where spillover is common. This means staying away from bat roosts and avoiding the consumption of unwashed or unpeeled fruits. Practical awareness is the most effective tool for those moving through these high-risk areas.

By identifying who is at risk, we can establish clear, actionable steps for prevention in our daily routines.

Protection and Prevention in Daily Life

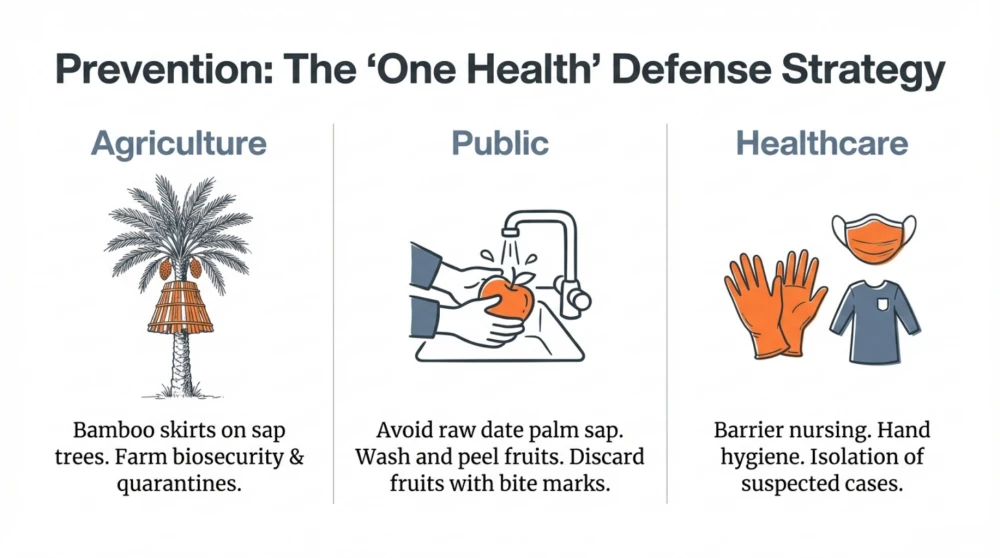

In the absence of a licensed cure, our primary defense is breaking the chain of transmission. We can transform standard medical precautions into simple habits that protect ourselves and our communities.

- Prioritize hand hygiene. Regularly washing your hands with soap and water is the best way to remove infected secretions that you may have accidentally touched.

- Be selective with date palm sap. Only consume sap that has been boiled, as heat kills the virus. If you are a producer, use "bamboo sap skirts" to cover collection jars and prevent bats from accessing the sap.

- Practice fruit safety. Thoroughly wash and peel all fruits before eating. More importantly, discard any fruit that shows "nibble" marks or signs of bat bites.

- Avoid contact with sick livestock. If pigs or horses in your area show signs of illness -- especially a barking cough in pigs -- avoid the area and contact veterinary authorities.

- Maintain distance from bat roosts. Do not touch surfaces that could be soiled by bat urine or saliva, and avoid areas where fruit bats are known to congregate.

While these measures provide immediate protection, the global medical community is also moving toward long-term scientific solutions.

Looking Ahead: Vaccines and Treatment

Currently, there are no licensed treatments or vaccines for the Nipah virus. Medical care is primarily "supportive," meaning doctors focus on keeping the patient hydrated, treating seizures, and using ventilators for respiratory distress. This lack of a specific cure is why research into new therapies is a global priority.

There is significant progress on the horizon for late 2025. A major collaboration between CEPI, the University of Oxford, and the Serum Institute of India is focused on creating an "investigational reserve" of the ChAdOx1 NipahB vaccine. This vaccine uses the same trusted ChAdOx1 platform found in the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, which helps build immediate familiarity and trust in its safety.

This reserve of up to 100,000 doses is designed to be deployed quickly during future outbreaks. By having these doses ready, the world can potentially halt an epidemic in its tracks while gathering the data needed for full licensing. Until these medical tools are ready, our strength lies in education and early reporting.

Key Points

- Nipah is a highly lethal virus (40% to 75% fatality rate) spread by fruit bats that causes severe brain swelling and respiratory failure.

- The virus often enters human communities through contaminated food, such as raw date palm sap or fruit bitten by bats.

- Pigs and horses can act as intermediate hosts; a "barking cough" in pigs is a key warning sign of an infection.

- Human-to-human spread is possible through close contact with body fluids, making strict hygiene and isolation vital during outbreaks.

- A major vaccine reserve using the ChAdOx1 platform is being developed for 2025 to provide a rapid global response to future cases.

Educational only, not a substitute for medical advice.

Dr. Pankaj Kumar Medical and Lifestyle Clinic